Reflections on the 2019-20 school year

- Andrew Meunier

- Jul 1, 2020

- 10 min read

Updated: Jan 22, 2025

The 2019-20 school year was one like no other. Glens Falls City Schools made the sudden switch to remote learning on March 16th due to the COVID-19 pandemic and remained closed until the end of the school year. My district had some distinct advantages in this challenging situation. We had been moving towards a 1:1 Chromebook model for a few years and all middle school and high school students already had a school-issued device. Many teachers already used the Google Classroom platform and most students were familiar with it before the shutdown. The same was true for Google Docs and PDF editors such as Kami. The sudden shutdown was jarring for many reasons but at least we didn't have to introduce students to these tools remotely.

In the first few weeks of the shutdown, we were told to suspend instruction of new content and instead review old material and encourage students to complete back work. I used the Chrome extension "Screencastify" together with Kami to create short review videos that I called "math blasts." I tried to keep these under 10 minutes and posted them on my Google Classroom pages. In each math blast, I reviewed a math concept and then asked students to try a problem similar to the one I had demonstrated. I then started each math blast with a quick explanation of the problem from the last video. I used a simple Google Form to have students register their completion of this exercise.

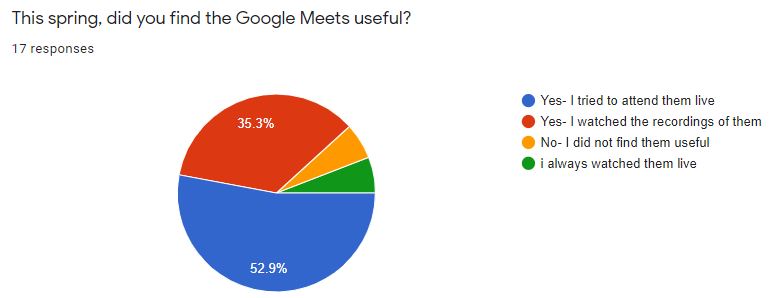

As the shutdown dragged on, we were told to resume instruction of new material. I began scheduling Google Meets with my classes (two per week) where I taught new objectives. I continued to post occasional math blasts and I used longer Google Forms to assess students's learning each week. Participation was disheartening at times; I never exceeded 50% participation and attendance was unpredictable (e.g., a student might participate for two weeks then disappear for the next three). I used a Google Sheet to track student participation and my outreach attempts. I had numerous phone conversations with parents and learned about the myriad barriers to remote learning. These included internet connectivity problems, unfamiliarity with online learning platforms, and busy parents who were unable to hold their children accountable for completing school work during the day. My Google Meets provided some revelations about the realities of students's home environments. On more than one occasion, I had to ask a student to mute themselves because the cacophony in their home was preventing me from teaching. In one memorable lesson, a students's bird was loudly squawking every few seconds! Younger siblings passed in and out of the video as did pets of all kinds. Sometimes I would end the Meet and sigh in relief, grateful for my quiet and controlled workspace.

Food Deliveries

Our district is not a wealthy one and about half of our students are eligible for free/reduced lunch. At the start of the pandemic, we distributed food to families in the school building but eventually had to transition to delivering food to families via school buses twice per week. I volunteered for this on two occasions, assembling food bags in the back a school bus and running the bags out to homes on our route. This work could be nausea inducing. I often felt like I was working inside a submarine or a poorly flown airplane. I was continuously juggling milk cartons and ricocheting off of sticky bus seats.

The undertaking was inspiring in some ways: we were helping families in need (irregardless of their free/reduced lunch status) and the operation was streamlined to an amazing degree in the end. Volunteers were abundant; teachers and support staff filled the online sign-up sheets within hours. However, I also found the whole situation disquieting. How did it come to be that our community was so food insecure? Why were we using diesel buses to deliver sugary cereals and dairy products packaged in layers of plastic bags to families? In most cases, wouldn't it be much more efficient to just give families cash or vouchers for food and trust them to use it to feed themselves?

Lessons Learned

Remote instruction was a challenge for me and I definitely had some stumbles along the way. Below are a few thoughts about what I've learned and how I might approach a similar situation in the future. Warning: lots of "teacher speak" ahead!

Syncronous vs. asychronous instruction

I surveyed my classes at the end of the year and there were mixed feelings about synchronous vs. asynchronous instruction. For example, about 40% of students in one of my classes seemed to prefer a mix of both. When I asked students, some favored asynchronous instruction (such as the math blast videos) as they could watch these whenever they wanted. This is another good reason to always record Google Meets so those students who couldn't attend could at least view the lesson.

Remote lessons require as much planning as regular lessons

As with any lesson, having a clear plan for my Google Meets was essential and meeting at the same time on the same days helped the kids establish a routine. I relied heavily on Google Drive to stay organized. Since Drive plays so well with Google Classroom, this was a big time saver.

Incentives

About halfway through the shutdown, I started raffling away a personal pizza each week from a local pizzeria. Students could get extra chances to win by attending Google Meets and completing assignments. This was a nice way to reward students who were working hard and there were some indications that students were motivated by it. Unfortunately, incentives like this wouldn't be sustainable if we were shutdown for months at a time again. In that case, I'll have to think more about how I can celebrate students successes. It's not lost on me that one reason students were unmotivated or difficult to engage this spring is that we (i.e., our educational system) has not done an adequate job helping students to cultivate intrinsic motivation for learning.

Paper materials

I've come to believe that if we use remote instruction in some form next year, my students with disabilities (and probably most students) would benefit greatly from having guided notes and prepared practice problems on paper in front of them in addition to digital resources. I doubt that most students took notes on their own paper when I was teaching (even though I asked them to) and the electronic resources I provided just didn't seem adequate. In math, there's currently no real substitute to working out problems on paper and it helps to have the student's paper mirror the instruction. I'm considering reviving the "unit packets" that I used to use many years ago because it would be logistically easier to distribute and manage these in a remote teaching scenario. These packets would have guided notes and practice assignments for an entire unit of study in one package. A major benefit of such packets is that they help students stay organized, an especially important factor during remote instruction. Packets also lend structure to student note-taking and anchor their attention in the lesson. When districts introduced the use of Google Suite products such as Docs, they likely thought that a decreased reliance on printed instructional materials would follow. Ironically, it seems that well-designed printed materials used in conjunction with digital tools could make remote instruction work more smoothly for my students.

Incorporating digital resources into paper materials

This summer I will create instructional materials that have blended paper and digital components. In the materials I've created so far, I've built Quizlet sets and included QR codes linking to them within the lesson materials so that students can scan these with their phones. I will also include hyperlinks so that if there are using the digital version of the packet or referring to a Google classroom post they can easily access the Quizlet set there as well. Even if we do not use remote instruction, these will be valuable resources for students and worth effort required to create them.

Games

Many games that I play with students in the classroom work remotely! The lessons where I played Gimkit with my eighth graders saw some of the highest levels of engagement. Other games like Kahoot are also well-suited to remote instruction. Unfortunately, I don't see a way to play Quizlet Live remotely which is too bad as this was favored by my eighth graders.

Planning and routines

I wish I had been able to present a more detailed long-term plan for students and parents this spring. I was too slow to adopt Google Calendar as a built-in planning tool for students. Eventually, I scheduled our virtual classes using the calendar and invited students as guests. If they accepted the request, the class was added to their calendar and they got an automatic reminder to attend. The reality of this spring was that there was so much uncertainty that putting together plans more than an week or two in advance could sometimes be counterproductive. If we do go back to in-person teaching in the fall, I'm planning on using tools such as Google Calendar from the onset so that students will be accustomed to these if we do need to use any remote instruction.

Assessment and feedback

Assessing students when teaching remotely remains a puzzle for me. Google Forms is an obvious choice for doing this as it gives students instant feedback and allows me to collect student responses easily. Unfortunately, these do not give me same quality of feedback that I am used to getting from students because they are not able to show their work and can often fudge their way through multiple choice questions. Open response questions in math are challenging to do with Forms. This spring I experimented with using a website called Edpuzzle to create videos with built-in assessments. I'm considering using these more frequently next year as a way to assess students because the format forces students to watch a video (it pauses if they open another tab or click away) and has them answer questions as they go. In this case, the video would simply be me reading and displaying problems. I like how I was able to use the video to scaffold problems for my students with learning disabilities. This is also a good option for my students who get assessments read to them. The Edpuzzle teacher dashboard is also quite good and gives me information about how long students engaged with the video and how many questions they attempted, solved correctly, etc.

Managing disengagement

A major concern of mine throughout the spring was the lack of participation from certain students. Sometimes no amount of calling home, emails, or even text messages could get them to engage in instruction the way I wanted them to. Unfortunately, it was my students with the most severe learning disabilities that engaged the least in my online instruction. I worry about how these students will be able to make progress if we must continue to use remote instruction next year. If we do use remote learning again, I'll need to identify these students early and do everything I can to make sure they (and their families) understand my expectations and exactly how to meet them. One mistake that I made this spring was making too many assumptions about students's abilities to manage their time and stay organized. I also assumed that families would take on responsibilities that many ultimately didn't. They may have simply not had the time or resources to sit with their child and help them to organize their time, access Google Classroom, or set up a suitable learning environment. It's also possible that they did not understand the tools we were trying to use to deliver instruction. With all the turmoil our community was facing, I was always very gentle when talking to families. This was probably the correct approach given the situation but I wonder if I should have been more persistent or insistent when having conversations with parents. If we use remote instruction again, I'll have to double down on clear and frequent communication, keeping in mind that families may not be familiar with the digital tools we'll be using.

What Could We Learn From This?

I'm hopeful that some good may come out of the changes we had to make this spring. At the very least, everyone is now more familiar with digital tools such as Screencastify, Kami, Google Classroom, and Google Meets. Proficiency with digital tools will be beneficial even if we don't use remote instruction again. Virtual IEP meetings proved to work surprisingly smoothly and could be a useful alternative to in-person meetings in some instances. I personally had better family participation in my virtual IEP meetings than I had during in-person meetings. Conversely, we've learned the limits of digital tools and might better understand the value of certain traditional methods. For example, tools like Kami are still too cumbersome for many math applications and I frequently missed the versatility of the humble paper worksheet.

The pandemic could also lead us to rethink certain institutions and practices that we previously took for granted. For example, parents and students watched as state officials canceled all state standardized tests. Where these tests seemed like an immutable fact of life a year ago, people may now be more open to questioning their place in our educational program. Similarly, a shift could be possible relating to our conversations about grading. My school leadership seemed motivated to make much-needed (but politically challenging) changes to school grading policies last year but these were mostly abandoned. This year, we had major disruptions to our normal grading practices. Third quarter grades counted as only 10% of students's course grade and the fourth quarter was graded as "pass" or "incomplete." If a student earned a "pass," teachers had the option of adding up to five points to their final course grade. The reasoning behind this choice was that a significant number of students were disadvantaged by a lack of appropriate work environment, access to WiFi, family members available to assist them, etc. and so should be held harmless if they were unable to participate fully during the fourth quarter. But many of our students face these significant challenges during "normal" times. How often do our current grading systems simply reflect the resources that our students have at their disposal? This spring also raised questions about the purpose of grades. Should they measure effort, mastery, or some combination of both? If we had thoughtful answers to these questions before the pandemic, our grading conversations this spring would have been less convoluted. It's my hope that exposure to a the "P" or "I" grading system might spark interest in revamping our current grading schemes and their dubious reliance on percentages.

What's Next?

As I write this, cases of COVID-19 are spiking across southern and western states that began reopening in May. Cases and hospitalizations in New York are low and falling. However, I am apprehensive about cooler weather and the danger of teaching indoors in a crowded environment. My district approved my plans to spend some time re-writing curriculum this summer with the hopes of entering the year prepared for whatever awaits us. Hopefully, I can apply the lessons we learned to make some useful updates. Perhaps we'll even look back on this time as an inflection point of sorts where we finally examined some of our longest-standing practices and tried to make changes that have the potential to benefit all students.

Comments